In the midst of the Eurozone “sovereign debt” crisis and increasing spreads in 2010-11, interbank lending came to a halt. At the same time, bank clients were moving funds from the banks of the countries “in trouble” to the banks based in “safe countries”. Because “core” banks were not willing to lend liquidity back to them, “periphery” banks borrowed from the Eurosystem to settle their payments, and Target2 balances diverged. This ended with Draghi’s “whatever it takes” announcement in the Summer of 2012 and the introduction of OMT in the ECB’s toolbox.

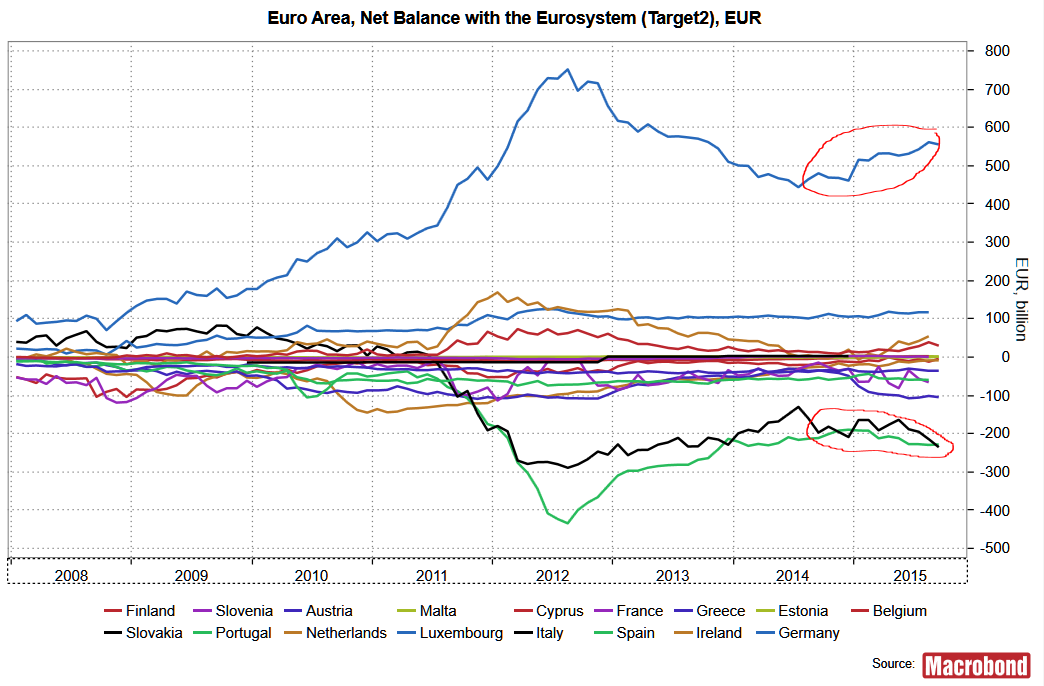

What is happening today (SEE CHART) is very different, and does not reflect a “flight to safety” as it did back then. Today’s divergence is a consequence of the ECB asset purchase program (QE), as well as of the current levels of policy interest rates set by the ECB.

The ECB is currently offering overnight credit to banks at 0.30%, is charging a 0.20% on overnight deposits in excess of any required amount, and offers liquidity in its weekly refinancing operations at 0.05%.

It seems that the bulk of the sellers of bonds to the ECB are clients of German banks (or banks in non-euro countries that are using German banks as correspondent banks). So banks settle the bonds for their clients, credit the account of their clients, and their liquidity balance goes up.

Because liquidity is more than banks need, most banks have no borrowing needs, and any excess liquidity is hardly loaned to other banks. Under conditions of ample liquidity, those few banks that need liquidity have two options: Borrow in the interbank overnight market for liquidity, where the interest rate is currently around -0.1%, or borrow at weekly ECB auctions at 0.05%.

What happens is that banks in the “periphery” would only be willing to borrow from German banks with ample liquidity at a cost that is less than 0.05%. Banks in the “core”, however, still perceive a counterparty risk on banks in the periphery, although much less dramatic than in 2011-12. And as long as their lending premium is high enough to make borrowing from the Eurosystem a more convenient option, banks in the “periphery” borrow directly from the Eurosystem. The result is that T2 balances in “core” countries go up, while T2 balances in the “periphery” go down.

In conclusion, the QE liquidity largely goes to banks in the “core” and sits there. This also means that “core” banks are the ones most penalized by negative rates.