In February 2011, I was in the audience of a lecture given by John Taylor on the “exit strategy”. One main theme was that the policy of the Fed called “Quantitative Easing” meant a high risk of monetization and inflation, if not hyper-inflation, in the U.S. economy. In the Q&A session, I asked Professor Taylor why he thought that “monetization” is inflationary. I argued that Quantitative Easing boils down to portfolio shifts in banks’ balance sheets, and that asset reallocation does not seem to be causing an increase in demand, nor a price increase. His answer (that I quickly noted in every detail on a piece of paper) was:

John Taylor’s answer: We do have theories that connect money to inflation. Yet, it is not simply this channel. it could be expectations. When excess reserves translate into money supply expansion, inflation becomes a risk. At that point, the Fed should reduce its balance sheet, but the question is how long will it take? Also, QE makes financial markets aware of a signal that interest rates will remain too low for too long. And please don’t forget the international effect: Emerging countries will find it more difficult to raise their own interest rates to prevent inflation, so inflation may spread from there. The inflationary effect of QE is not instantenous, although we begin seeing it now in commodity prices. In any event, inflation risk remains a concern.

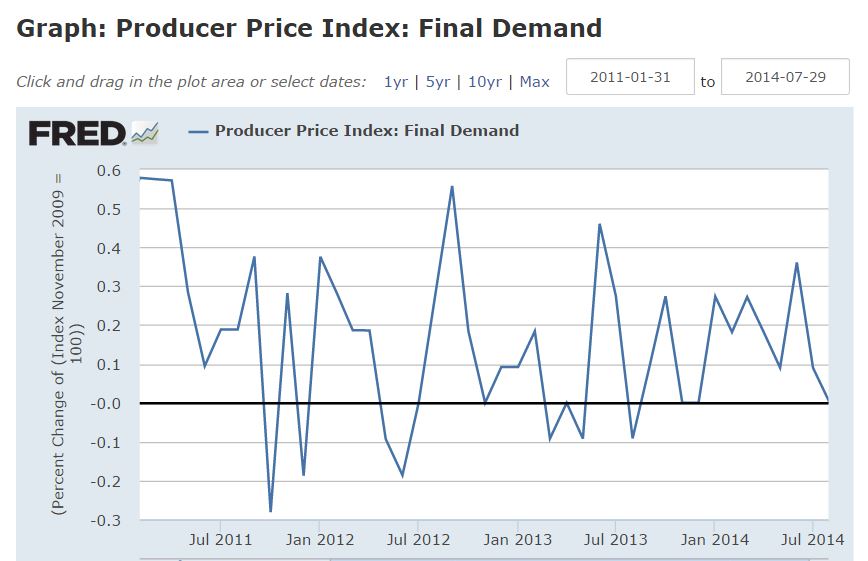

The fact is that since John Taylor’s strong forewarning of rising prices, and after a lot more QE by the Fed, U.S. inflation has always been lower than it was at the time he delivered this speech. Three and half years later (see Chart), we don’t yet see evidence of John Taylor’s feared inflation.